Buckingham Square: One of Hartford's Smallest Parks

Although tiny, the park has had its share of big controversies over the years.

At the northwest corner of Main Street and Buckingham Street in Hartford is a small city park, surrounded by a fence. It’s only about 100 feet long and maybe 35 feet across. It exists because of the unusual location of a now lost building that was torn down in the 1820s. Despite the park’s diminutive size, it has occasionally been the subject of fierce debate in the community during the nearly two centuries since it was officially established back in 1830.

The Park is There Because of a Lost Church Building

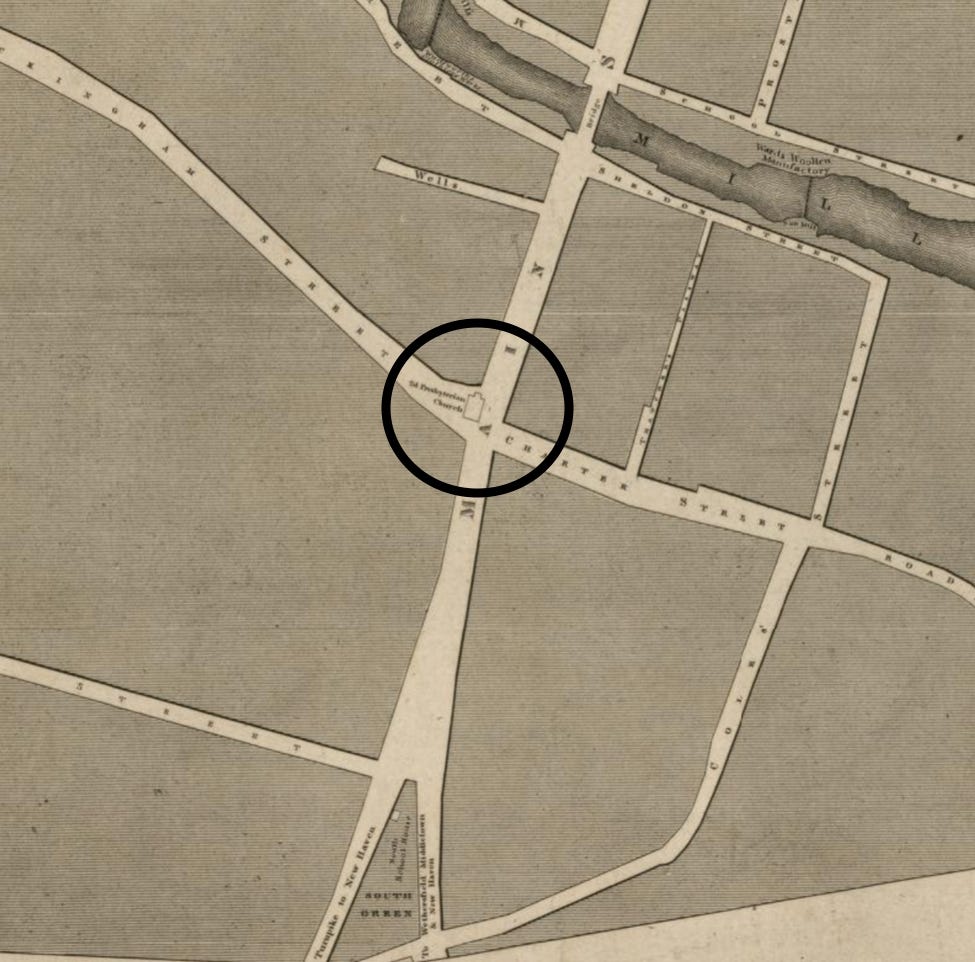

In my recent video on a section of Hartford’s Main Street in 1774, I talked about the fact that South Congregational Church, now located at the southwest corner of Main and Buckingham Streets, had an earlier meeting house that stood right in the middle of the entrance to Buckingham Street. Built in 1752-54, the South, or Second, Church of Christ’s meeting house faced north, with its east side sticking out a bit into Main Street. For over seventy years, if you had wanted to turn onto Buckingham Street from Main, or cross Main to get to Buckingham from what’s now Charter Oak Avenue, you would have had to go around either the north or south end of the church to continue on your way westward. This was quite an obstacle! The growth of city traffic in the early nineteenth century, combined with the South Church congregation’s need for a newer building, led to the construction of the current church on the corner in 1825-27. The old church was taken down, thus removing the obstruction to traffic, but part of where it once stood would become Buckingham Square Park.

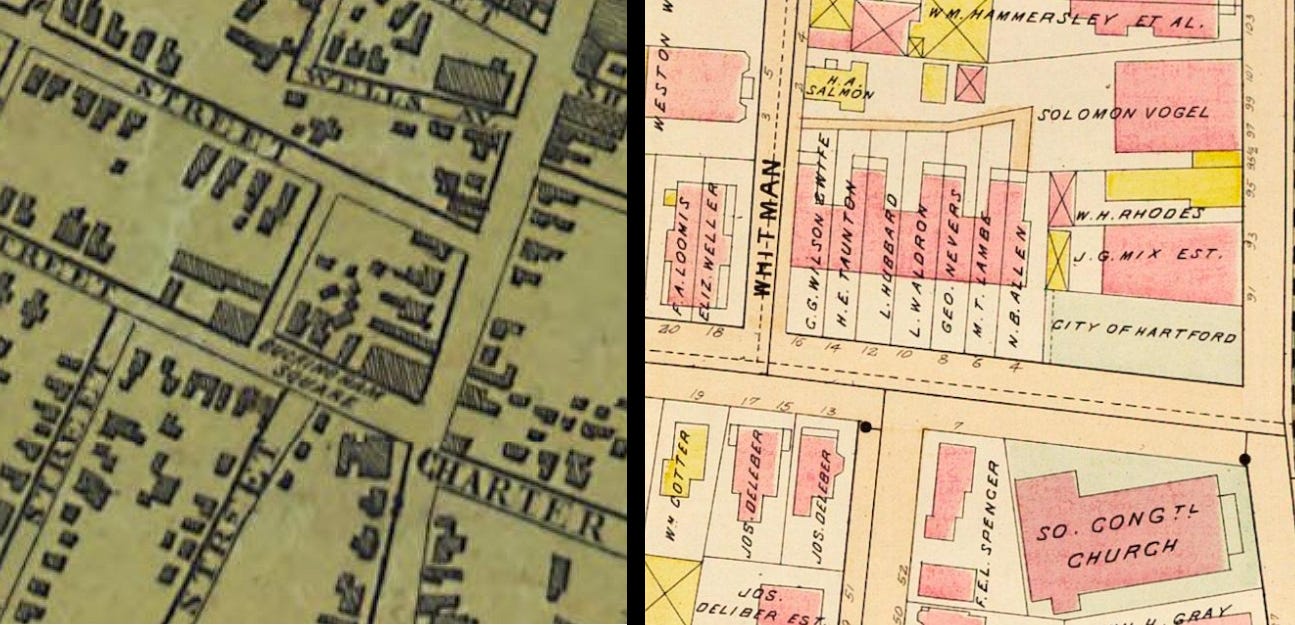

Originally, Buckingham Street followed a diagonal path and its western end reached Trinity Street about where Capitol Avenue does today. Its eastern end widened at the intersection with Main Street, forming a chamfered corner to accommodate the presence of the church in the road. After the old church was removed in 1827, Buckingham Street was re-laid south of its original path and now follows a straighter course from its intersection with Main. Part of where Buckingham Street once widened out, where the northwest corner of the church stood, a public square was laid out in 1830. Called Buckingham Square, it extended along the north side of Buckingham Street from Main Street, west to Whitman Court. In 1865, an impressive row of seven three-story townhouses was erected on the north side of Buckingham Street, facing the western half of Buckingham Square. This section of the square is now the front yard of these rowhouses, while the section of the square at the corner is owned by the city as Buckingham Square Park.

Early Controversies of Buckingham Square Park

The 1911 publication, History of Hartford Streets, compiled by Albert L. Washburn and Henry R. Buck, notes that Buckingham Square was laid out as a public square on the petition of Isaac Spencer, John G. Mix and others. According to the petition, the square was “susceptible to being ornamented by setting out a row of elm through the center or on each side of same, thereby making it ornamental to the city.”

John G. Mix operated a grocery store on Main Street, just north of Buckingham Square. In 1845 there was controversy over Mix’s desire to set up hay scales on part of the square adjacent to his store. This was resisted by the neighboring South Congregational Church. The conflict seems to have gone on for some time. On October 7, 1846, after the City Council postponed action on a by-law requiring that city squares be enclosed, the Hartford Courant ran a piece by an anonymous citizen who wrote:

For a long period, whereof the memory of man hardly runneth to the contrary, Buckingham Square, has in one way or another, been a topic of sharp controversy. In times well neigh numberless, the matter has been before the Council, and in almost every report of the doings of the City Fathers, is a paragraph in relation to Buckingham Square, and “them scales.”

Four decades later, the western 5/8ths of Buckingham Square, in front of the rowhouses, had become a lawn with crosswalks and low wooden railings put up by the homeowners to connect to Buckingham Street. According to an 1884 report by the Park Commissioners to the Council, “The rest of said square is in an unfinished condition and quite barren and rough.”

The building to the north of the rough part of the square was owned by the Mix estate and was still being used as a grocery store. In 1888, the city filed suit against the estate for encroaching on the park. The store had hitching posts at the rear of the building and often “teams were driven across the Main street sidewalk and the east part of the park practically made a gangway to serve the convenience of the grocer occupying the store.” The city wanted to landscape this rough section of the square, but a Judge ruled that the grocer was within his rights to cross this public property for his private business.

The city’s Board of Street Commissioners decided to move ahead with plans to lay out a public park along Buckingham Square, setting aside a 10-foot-wide strip on the north side for the grocer’s use as a driveway. The grocer immediately objected that this would not be nearly wide enough. He was not the only one to have strong opinions about the Board’s plans. In sometimes heated testimony, various witnesses appeared before the Board to argue whether the proposal would damage the value of the Mix property. Among those who testified was architect John C. Mead, who “gave it as his opinion that the proposed layout of Buckingham square as a public park would injure the property very materially.”

Miss Susan B. Hubbard, who along with her sister owned the block of rowhouses, also objected to having the park, “right under her windows.” She was alarmed that disabled people might gather there,

And then there were the nurse girls and the babies and the baby carriages and the wicked little boys playing marbles; and again, there were the peanuts! Another objection urged by the witness was that babies would often be left right on her steps. “Take them into the house, then,” urged President Sprague, “The poet says that a baby is a well-spring of joy.” “Oh, but it might cry and that would be worse than leaving it out of doors!” was the horrified reply.

The city would get its way and the eastern half of the park at least, adjacent to the Mix estate, was graded and turfed in 1890.

As a piece in the Courant, on April 24, 1913 observed:

It doesn’t seem possible that Buckingham square, with its one-third acre plot, ever looked more attractive than it does this season. With its hundreds of vari-colored hyacinths in central beds and its border of smaller plants, the landscape effect is most beautiful and the garden of flowers commands the attention and admiration of hundreds of people every day. The fragrance of the hyacinths is noticed long before one comes within sight of the garden. The flowers are now at their best in form, color and perfume.

It was about the time this article was published that benches were placed in the park.

Trouble Over the Benches (1930)

Buckingham Square Park was again in the news in the wake of the 1929 Stock market crash and the onset of the Great Depression. On September 19, 1930, the Courant ran a letter from an indignant young man who signed himself “One of the Unemployed.” He had been riding on a streetcar that went by Buckingham Square Park. When the two women seated across from him observed the out-of-work men who were sitting on benches in the park, he overheard their conversation. One of them dismissed the men as lazy because they were sitting around smoking and reading instead of looking for work and the other woman agreed, concluding they must not want to work, because there was plenty of work for those who cared to look for it. The first woman then declared that they were all bums and there should be laws to stop them from sitting around in public places.

In his letter, the young man lamented the women’s ignorance and lack of compassion. He felt that these men, like himself, had likely been up at 6 a.m. to pour over the want ads in the paper and had then made fruitless visits to the employment agencies. By 10 o’clock, there was no use looking elsewhere until the evening paper came out, so they sought some respite in the park, where they could talk to other men to help pass the long day. For that they were being dismissed as bums! Some of them may even have been veterans who had sailed to France in 1917 to fight on behalf of the same general public that now condemned them! (The young man did admit that there might have been some “bums” in the park, “but the percentage is less than one-half of one, and they are of the foreign-born element.”)

The two women were not the only ones who felt something should be done about the men who gathered in the park each day. Rev. Warren S. Archibald, pastor of South Congregational Church across the street, wanted the benches removed. He complained to the city’s Board of Park Commissioners “that the animate and inanimate aspects of the park do not make suitable surrounding for the church, its newly landscaped grounds, and for the 500 small children who attend Sunday school.” Spurred to action, in November of 1930, the Board instructed Superintendent of Parks George H. Hollister to prepare plans for a beautification of the park without any benches.

The proposal to remove the benches from Buckingham Square Park roused the Hartford Central Labor Union to protest. In a statement, the organization noted that one of its former presidents,

Albert P. Krone, while an Alderman in the City Council from April 2, 1912 to April 2, 1914, was instrumental in having the benches placed in that park, so that any citizen could rest if they cared to. If it is true that loiterers fill some of these benches and some of the frequenters are not a credit to the park, then we are satisfied that the Hartford Police Department is capable of correcting this condition upon complaint to the Department. The same is true of all parks. Why not remove all the benches in all parks?

The statement also observed that, “When any park or any institution or anything else is banned to occupancy by the citizens, then it ceases to be a beautiful spot or a credit to a municipality.”

The Central Labor Union was the sole voice in favor of retaining the benches. At a meeting on December 1, 1930, the Park Board voted unanimously to improve the square and remove the benches. A number of citizens who attended the meeting, including Rev. Archibald, expressed their support for the benches’ elimination. One resident of Buckingham Street argued that for years the square had been a “hang-out for drunkards,” who frequently defied the police. He urged the Board to “leave no benches for them to sit or lie on and leave no fences low enough for them to lean on.”

Another resident claimed that the “loafers” preferred Buckingham Square to other parks because it was near John Street, which he identified as the “wholesale ‘hooch district.” Some men would bring bottles back from John Street to consume in the park, while other times “the John Street liquor peddlers deliberately came to the square to dispose of their wares.” On December 3, the Courant printed a letter, signed Pyrrha, who noted that women, including mothers pushing baby carriages, found the park distasteful because of the men sitting there who leered at them.

Today the park, which is surrounded by a fence, remains benchless. The South Downtown Neighborhood Revitalization Zone undertook a clean-up and restoration of the park in 2014 and the city placed a new sign just inside the fence as part of a city-wide program in 2020. The sign gives the name of the park and the date of its establishment back in 1830.

I walk by this park every single day on my walk Very interesting to read about the history of this park and the complaints of the benches, I was born in Hartford 1980 and I remember this area all my life and I’ve always questioned this area and to see it sits to this very day without no benches and a drug treatment facility right next-door to it. I always wondered about the brown stones that stood right behind it.