The 1892 Mystery of a Little Girl Abandoned in a Hartford Hotel

A woman checked in with a 5-year old girl. The woman vanished and next evening the girl was found locked alone in the room. Who were they and what was the story behind this bizarre incident?

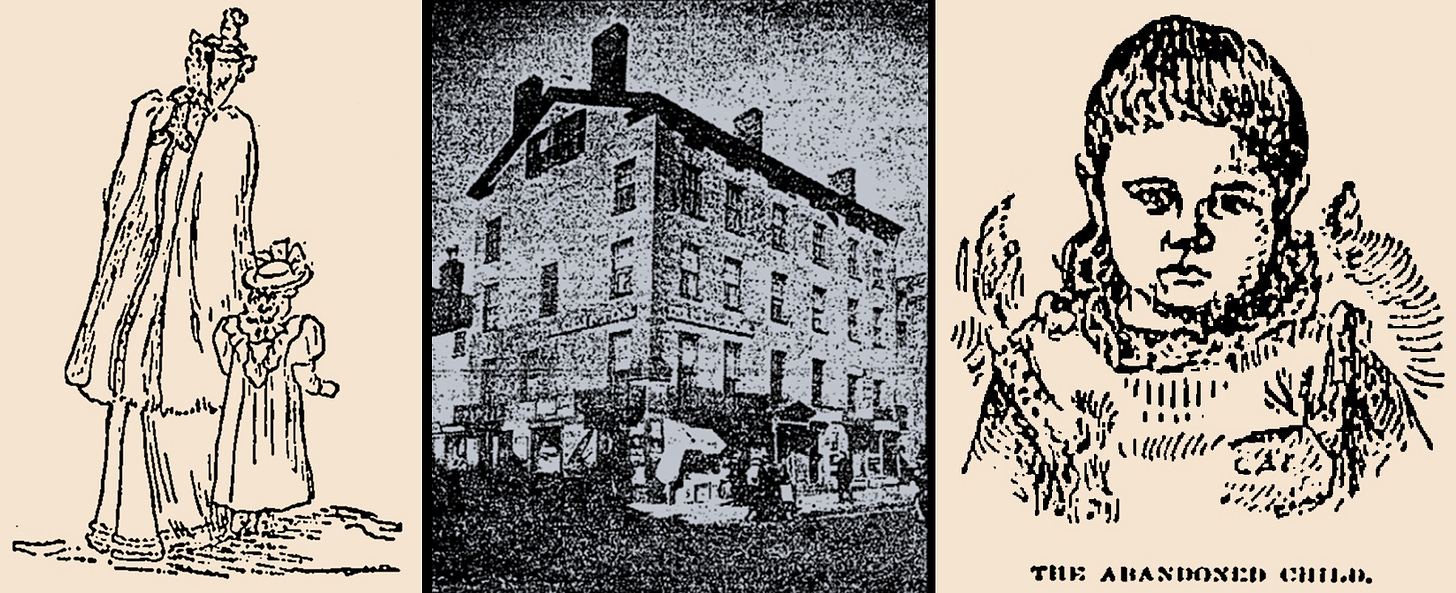

In November of 1892, a new column made its first appearance in the Hartford Courant. Entitled “Daily Dress Hint,” it was signed “F.” and would appear regularly for nearly two years. Every column featured a detailed piece of advice relating to women’s fashion, illustrated with a picture drawn by the columnist. For the November 24 column, the author presented a rear view of a mother and young daughter. The mother wore “a cape of long-haired cloth with silk lining and a trimming of Turkish edging,” while the child wore a mantle with “frills of the same stuff as trimming along with tight sleeves and puffs.” Explaining that the back of the woman’s garment was “part loose, part tight and part Watteau,” the author admiringly noted that the outfit “does not outline the wearer’s form but it makes her a graceful and alluring mystery.” This was because “a garment that clings nowhere, yet follows everywhere, suggests a thousand graces that disclosure of line might dispel, and guarantees all that is necessary to set the pleased imagination at work.”

Arrival of a Mysterious Pair

By coincidence, that day after this column appeared, on the morning of Friday, November 25, 1892, a woman and a young girl alighted from a train at Hartford’s Union Station. I don’t know if the woman’s garments would have excited F’s imagination (she was later reported to have been “of respectable appearance and comfortably dressed in black, wearing a dark derby hat”), but the question of her identity would indeed be a mystery for several days. Leaving the station, the pair made their way westwards down Allyn Street towards Trumbull Street. [Allyn Street ends at Ann Street today, but before the construction of the XL Center, it used to extend all the way to Trumbull Street (as I’ve described in a YouTube video).]

Reaching Trumbull, the woman and girl entered the first hotel they had come across, the Pratt Street House, which was at the northeast corner of Trumbull and Pratt Streets. As reported the following Monday in the Hartford Courant, the woman signed the register as “Mrs. Ray Johnson and child.” Although the child called her “mamma,” it was reported that “she gave no remarkable signs of maternal affection.” After being shown their room, the pair came down at noon and ate dinner [dinner referred to the main meal of the day, which took place at noon in those days; the evening meal was called supper]. The woman’s lack of maternal behavior was again noted, as it was observed, “she did nothing in the way of preparing the child’s food.”

The woman then brought the girl back to their room and left her there, locking the door behind her as she left. She when down to the office and asked the clerk “if there were good precautions against fire in the hotel.” The clerk assured her that “things were safe on that score.” The woman then went outside. As the Courant reported the following Monday:

Neither of these guests appeared at supper Friday night or breakfast Saturday, and at 10 o’clock that morning a servant was sent to investigate. The door was locked and the key taken away. The servant girl entered the room with a pass key. The little five-years-old was the only occupant, and all that was there besides the furnishings of the room, were the clothes on the girl’s back. The only sign of the bed having been used was a little depression where the girl had rested on the outside.

The child had had nothing to eat since the noon previous, yet she had made no outcry or sign that she was in trouble. In this and other instances she showed herself trained by an evidently hard experience to take quietly what was given her, but to make no protests or objections.

The hotel’s matron, Mrs. Dr. Black, cared for the abandoned child and, together with the manager, Mr. Kingsley, were able to coax from her that her name was Etta “Papel” and that she lived on Seymour Street in Bridgeport, Connecticut.

A Strange Tale in Bridgeport and a Trip to New Haven

Five years earlier, a young Bridgeport woman had given birth to a baby girl. Sadly, the young mother passed away three months afterwards. The child’s father was unknown, so a year later she was adopted by Christian Peppler and his wife, who had no children of their own. They named their new daughter Johnetta. The couple lived on Seymour Street in Bridgeport and Mr. Peppler went to work each day in Saugatuck, in the town of Westport. His wife was a seamstress. On that particular Friday, he returned home to find his daughter was gone and his wife, who had just arrived home herself, frantically calling for the police to find her child. She had quite a tale to tell.

According to Mrs. Peppler, a messenger had arrived at their home that morning with a note. It instructed her to bring Etta to the railroad station right away to meet the mother of their child. The note was signed “Baby’s mother.” Although Etta’s mother was known to have died almost five years earlier, Mrs. Peppler decided to go to the station and to bring the little girl. She later made the peculiar statement that she and Etta had made their way there in “different directions.”

At the station she met a woman, so the story goes. She went a ways down Fairfield Avenue with this woman and took some coffee with her. Too late she discovered that that coffee was drugged. She could remember that she went on the train with the woman to New Haven, and that she went to some house there, and that in the afternoon she became master enough of herself again to take a train to Bridgeport.

After hearing his wife’s bizarre story, Mr. Peppler contacted the police. Officers soon went out to question witnesses in the vicinity of the station. They returned with a report that Etta had been seen that morning seen in front of a candy store talking to two women, one who had red hair.

Mrs. Peppler “thought that she could remember the house to which she went in New Haven, and so on Saturday she and her husband went over to that city and took Detective Arnold along with them.” When they reached New Haven, though, she “lost her bearing altogether.” After a long and fruitless search, the two men had to turn their attention to Mrs. Peppler because she had “gone into hysterics.” Her husband explained that Mrs. Peppler had been injured “in a runaway accident two years ago and any excitement was dangerous for her.”

There Had Been Tension in the Peppler Household

When they reached home, Mrs. Peppler was in “quite a serious condition.” Although he was anxious about her health, her husband could not quiet his suspicions about her strange story. That evening he “expressed the opinion that his wife knew more about and had a great deal more to do with the disappearance of Etta than she was willing to admit.”

As the Courant reported, a tension had been growing in the Peppler household. Since Etta’s arrival, both parents had showered attention on the child, but

She was an odd little chick and very cherry of her affections. In fact, she seemed to have little affection for anyone but Christian Peppler, and there’s where the trouble that this story tells seems to have begun. The mother failed in whatever artifices she may have tried to win the child’s heart, and then she stopped trying, watched the goings on between the little thing and her adopted father and saw that the child loved him and did not love her.

The Courant reporter spoke to one relative of the family who had visited the house enough to form the opinion “that there was trouble brewing from this state of things.” This relative once heard Mrs. Peppler say to her husband, “Other people have some claim upon that child.”

A Reunion in Hartford

On Sunday night, Mr. Peppler was planning to return the next morning to New Haven and then to go on to Hartford, where he’d “look in the Roman Catholic asylums, into which stray children find their way.” But then a message arrived from the Courant, and he was soon on the “owl” train directly to Hartford, arriving at 2:20 AM Monday morning. Heading to the Pratt Street House, he quickly confirmed that the abandoned child was indeed his daughter. One strange fact was that Etta was wearing a different dress than the one she had been wearing when she’d left home. Mr. Peppler said he had never seen the new dress in their house.

Later, Mr. Peppler and Etta went to the offices of the Courant on State Street. Before Mr. Peppler left Bridgeport, his wife had denied having ever been in Hartford. When he was shown a description of the woman who had taken Etta to the Pratt Street House, he declared that it was not his wife. Convinced now of her innocence, he explained his own theory “that it was a carefully planned and well executed abduction.”

Mr. Peppler explained that three years earlier, a red-haired woman had abandoned her one-year-old son at Lane’s Candy Store in Bridgeport. He now conjectured that this woman had sent the note to the Peppler home, mistakenly believing that they were the couple who had adopted her son. While the woman drugged Mrs. Peppler and took her to New Haven, an accomplice had lured Etta away and brought her to Hartford. When the accomplice realized that the child she’d abducted was not the correct child, being a girl and not a boy, she then abandoned her at the Pratt Street House and fled.

Mr. Peppler must have been trying very hard to come up with some story that would exculpate his wife, but he had fully convinced himself. As the Courant reported the following day, he expected to get the truth from Etta during the train ride home, saying “She is scared now, but when we are alone I will find out who took her away from home, and if it was her mother I shall know it.” A Courant reporter accompanied them back to Bridgeport and within a short time “ascertained the true facts of the case.”

The Truth Comes Out

Etta was exhausted, but in the time before the train left she was able to sleep awhile lying down on two chairs and an overcoat. But “Once on the cars, her tongue was never still a minute, and her prattle was listened to with more careful attention than it doubtless usually receives.” The newspaper gave her story in her own words:

Mamma went with Etta all the way to the cars. When we came to Hartford we left the cars and walked down a straight street. After dinner mamma said her head ached. She would go out and get some air and Etta was to keep quiet till she came back. Etta waited and finally went to sleep. When she waked up it was dark. She thought she was in her own home and papa hadn’t come yet. She lay down and went to sleep again, and when she waked up someone was pounding on the door.

Confronted with Etta’s story, Mrs. Peppler finally admitted to being the one who took the girl to Hartford. She had completely made up the tale about the mysterious woman who had drugged her and taken her to New Haven.

That previous Friday morning, Alice Lee, a young woman who worked for the Peppler family as Etta’s nanny, had dressed the girl in a plain gingham dress. When Mrs. Peppler, who was a dressmaker, took Etta to the train station, she’d concealed under her cloak a Scotch wool dress she had made for a neighbor’s child. When they arrived in Hartford, she took Etta into a toilet room and changed her clothes, putting on her the hidden dress. Leaving the station and heading east, she then hurried into the first hotel she came across, where she took a room, came down with her daughter for dinner, and then left her there. Mrs. Peppler had to move quickly: She had less than two-and-a-half hours in Hartford before she had to catch the express train back to Bridgeport.

Mr. Peppler told the Courant reporter “that for some time past his wife has been subject to temporary fits of insanity,” during which “she is not accountable for her actions, which have often been very queer.” He was under great strain: “Mr. Peppler is thoroughly worn out with anxiety and fatigue,” but he declared, “he will see to it that no further opportunity is given for harm to come to his adopted child.”

The author of the Courant article felt that “How far Mrs. Peppler should be held responsible for her unnatural act is a question,” noting that “She is of an extremely jealous disposition, her nerves are unstrung and she seems shattered in mind and body.” The author concluded, “Charitable people will think that her mad acts were but the result of a disordered and deranged mind; others will always claim that she attempted to rid herself of her child through motives of jealousy and scrupled at nothing to accomplish this end.”