Throwing Red Hot Rivets Above Hartford

Over a century ago, the standard method for putting up the steel structure of skyscrapers involved workers tossing blazing hot rivets across long distances.

In yesterday’s newsletter I wrote about the construction of the American Industrial Building, a now lost 15-story Hartford office tower that was built in 1920-21. An article in the Hartford Courant on November 21, 1920, describes a visit by a reporter to the construction site. Climbing to the top floor of the partially completed building, he observes, as he goes higher, that “the stairways are less protected, the walls are open, only a rough layer of planks cover the girders and the uprights stand out in relief against the sky.”

In this challenging environment, he notes the daring bravery of the ironworkers, who boldly walk, rather than crawl, along the girders hundreds of feet above Main Street. He writes that “this daring, because it gives confidence, perhaps saves more lives in the long run than would be lost by too much caution.”

They know that lack of confidence begets inefficiency that is as perilous to the workmen as it is to the proper handling of the work itself. High above the din of traffic and the murk and smoke of the city these men live in a world of their own. They move swiftly and withall silently except for the occasional r-r-i-i-p-p of the riveting machines. They seldom talk loudly for fear of distracting others in perilous places.

These skilled workers of a century ago performed dangerous tasks long before the introduction of modern safety equipment:

The men, who operate the derricks, connect the girders, throw the rivets, catch the rivets and finally drive them in place must do so with the utmost precision and skill to avoid endangering other workmen about them, and especially below them. Each man must think of another’s safety as well as his own.

Hot rivets were the standard method to connect segments of structural steel in skyscrapers during the first half of the twentieth century, including the towering buildings of Manhattan. By the 1960s, rivets were mostly being phased out in favor of high-strength bolts, but for decades ironworkers had worked in teams to get the hot rivets in place before they cooled. As described by the Courant reporter who visited the American Industrial building, one man heated the rivets until they were glowing and then had to accurately throw them sizzling through the air:

Spitting out sparks and fairly alive with heat it sails with the curve of a comet’s tail into a tin bucket. The pitcher puts it over the plate every time and the catcher folds it in the tin mitt without fail. A third workman flicks it out of the pail in a jiffy, before it has a chance to cool, and a fourth drives it home in the girder to the accompanying roar of the riveting machine.

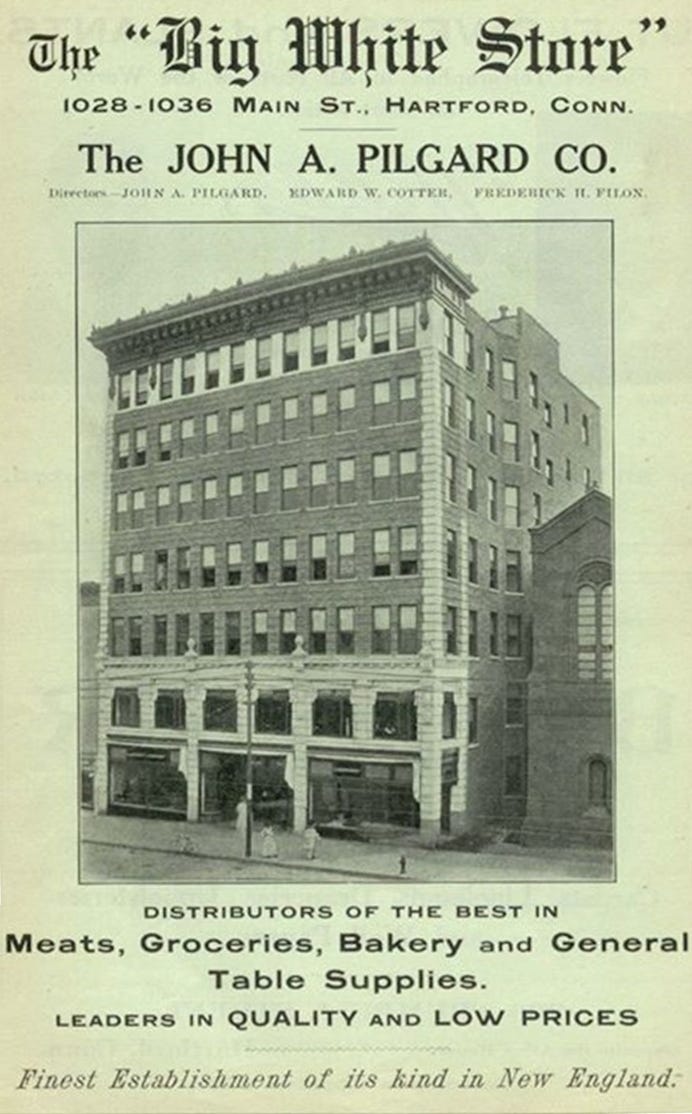

The 1920 article about the reporter’s visit to the American Industrial reminded me of another description of hot rivets in a Courant article from almost a decade earlier. In 1911, Danish immigrant and prominent Hartford grocer John A. Pilgard (who was also elected president of the American Industrial Company in 1921) erected a now-lost 7-story building on the east side of Main Street, between Talcott and Morgan Streets. The building’s steel framework had nearly been completed when the Courant reported, on August 10, 1911, that crowds gathered daily to watch the spectacle:

This is the most interesting of all sights in the construction work—the throwing of red hot rivets from the forge of the iron workers to the men who place them, joining beam to beam and flattening the new head. he distance that one of these rivets was thrown yesterday was from twenty to thirty feet—from the eleventh story to the fifth story—and, perhaps, forty feet, the entire width of the building. The rivets are thrown from thongs and are caught in large black pails.

The sight of a red hot rivet passing through the air and a man standing on a six-inch beam several stories above the earth, prepared to catch it, is enough to send a thrill through any of the onlookers, but apparently the men engaged in the business take to the work as a child does to a rubber doll.

The story also gives an example of the danger when a hot rivet was not caught:

One of the rivets, instead of landing in the catcher’s pail yesterday afternoon, struck the roof of the temporary structure of Pilgard’s grocery store. In a few minutes the front part of the roof was on fire. Several of the iron workers, after sliding down two and three beams, extinguished the blaze.